3: Functions#

Learning goals:#

Explain why we need functions in our programs

Identify key components of a function in Python

Construct a function block, from scratch

Convert existing code to a function

Use a function

Identify common errors with functions

What are functions and why do we care about them?#

Functions are basically machines that take some input(s), do some operations on the input(s), and then produce an output.

Why we need functions:

Model your problem so that it can be solved by a computer well aka Computational Thinking

Make fewer errors (reduce points of failure from copy/paste, etc.)

Motivating example: simple data analysis pipeline to compute percent change in revenue from last year.

We have two sales numbers

last_year = "$150,000"this_year = "$230,000"

Q: How can we analyze them? What are the subproblems here that we’ll need to solve?

A:

Two main substeps:

CONVERT strings to integers

COMPUTE the percent change

Here’s an example program that could solve this problem:

1# DEFINE the two sub-functions we need

2

3def clean_sale_number(saleNumStr):

4

5 # 1: remove dollar signs

6 saleNumStr = saleNumStr.replace("$", "")

7

8 # 2: remove the comma

9 saleNumStr = saleNumStr.replace(",", "")

10

11 # 3: convert to float

12 result = float(saleNumStr)

13

14 return result

15

16def compute_percent_change(lastYear, thisYear):

17

18 # first make the input numbers actually numbers

19 lastYear = clean_sale_number(lastYear)

20 thisYear = clean_sale_number(thisYear)

21

22 # then compute the percent change

23 result = ((thisYear - lastYear)/lastYear)*100

24 return result

25

26# actually use (CALL) the functions.

27

28lastYear = "$500,000.35"

29thisYear = "$1,256,000.21"

30percentChange = compute_percent_change(lastYear, thisYear)

31print(percentChange)

151.19986616009368

Without functions, we would need to copy/paste the clean sales operation. This is both annoying and increases the likelihood of errors!

1def compute_percent_change(lastYear, thisYear):

2

3 # make the input lastYear actually a number

4

5 # 1: remove dollar signs

6 lastYear = lastYear.replace("$", "")

7

8 # 2: remove the comma

9 lastYear = lastYear.replace(",", "")

10

11 # 3: convert to float

12 lastYear = float(lastYear)

13

14 # make the input thisYear actually a number

15

16 # 1: remove dollar signs

17 thisYear = thisYear.replace("$", "")

18

19 # 2: remove the comma

20 thisYear = thisYear.replace(",", "")

21

22 # 3: convert to float

23 thisYear = float(thisYear)

24

25 # then compute the percent change

26 result = ((thisYear - lastYear)/lastYear)*100

27 return result

You’ll really start to feel a practical need for functions once your programs start to approach a regular level of complexity, starting in Module 2 or so.

But it’s a fundamental concept for computational thinking (specifically problem decomposition), so it’s worth encountering it early, so we can start drilling that way of thinking. It also makes the PCEs a little less confusing!

Let’s take a closer look at what a function actually is in Python.

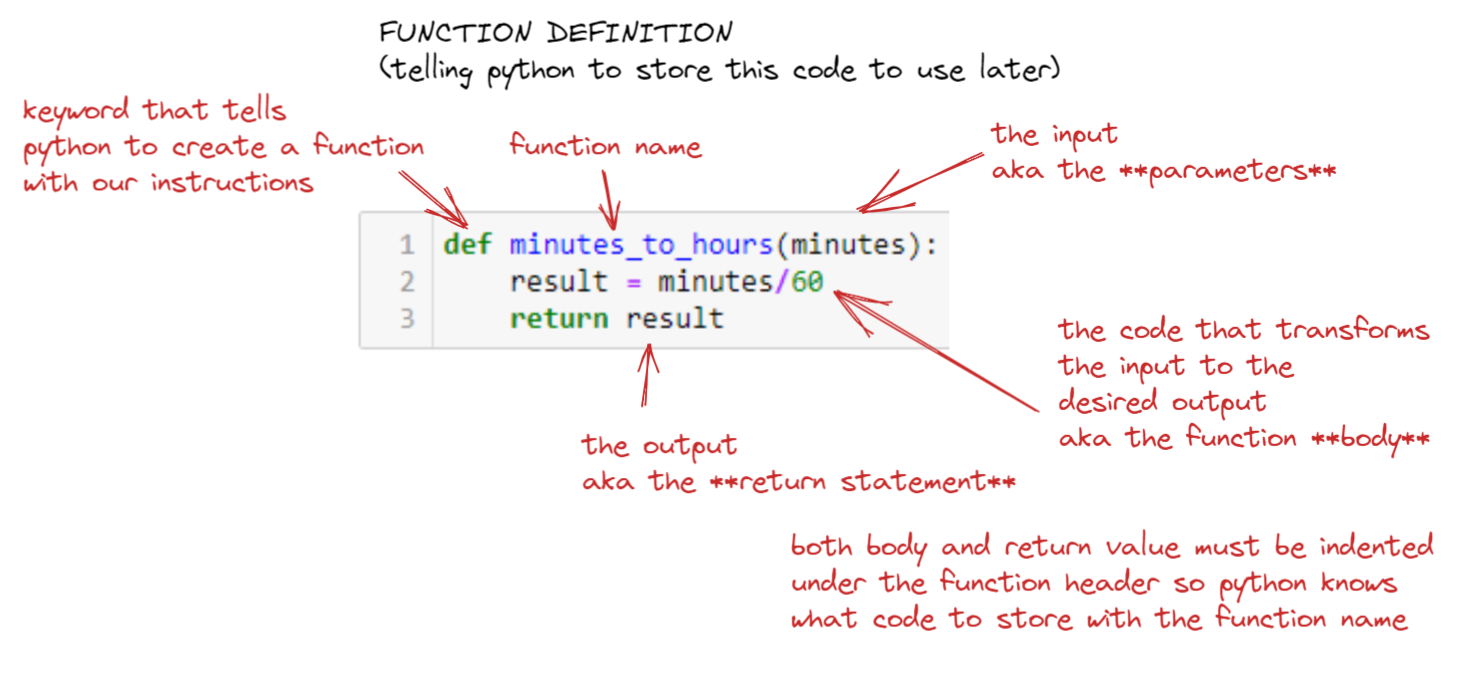

Function definition#

In Python, a function consists of three main components:

Parameters: what are the main input variables your function will be manipulating?

Body of the function: what operations will your function be performing on/with the input variables?

Return value: what will your function’s output be (i.e., what will come out of the function to the code that is calling the function)?

Let’s consider an example of a function to convert minutes to hours.

1def minutes_to_hours(minutes):

2 result = minutes/60

3 return result

The function minutes_to_hours() has input parameter minutes, a body of code that divides minutes by 60 and stores it in the variable result, and a return value that is the value of the variable result

So that’s the conceptual bits of a function. There’s also the syntax bits that make up a function definition. To see what they are, let’s compare the function definition to two other function definitions.

1def greet_user(username):

2 msg = "Hello " + username + "!"

3 return msg

1def longer(inputString, howMany):

2 toAdd = "a"*howMany

3 result = inputString + toAdd

4 return result

There’s a fair bit to notice here.

Q: What do you see here that you think is important?

A:

def

return, indented under the function name

name of the function

parentheses after the function name

one or more parameters inside the parentheses

colon

indented code as the body of the function (everything between the colon and the return statement)

Let’s practice with another function definition.

1def greet_user(username):

2 msg = "Hello " + username + "!"

3 return msg

Q: What are the parameters, function body, and return value(s) here?

A:

Parameter(s): username

Function body:

msg = "Hello " + username + "!"Return value: msg

And another example:

1def longer(inputString, howMany):

2 toAdd = "a"*howMany

3 result = inputString + toAdd

4 return result

Q: What are the parameters, function body, and return value(s) here?

A:

Parameter(s): inputString, howMany

Function body: lines 2 and 3

Return value: result

NOTE: when you run a function definition, there should be no output. The same thing is happening as with a variable assignment statement, like a = 3. Python is storing the code in the function body (and its associated parameters and return values) to be used later, just like with a = 3, Python is storing the value of 3 in the variable a to be used later.

So. When you write a colon after a function name, and indent code after it, it’s equivalent to an assignment statement (you’re assigning the code body and return statement to the function name).

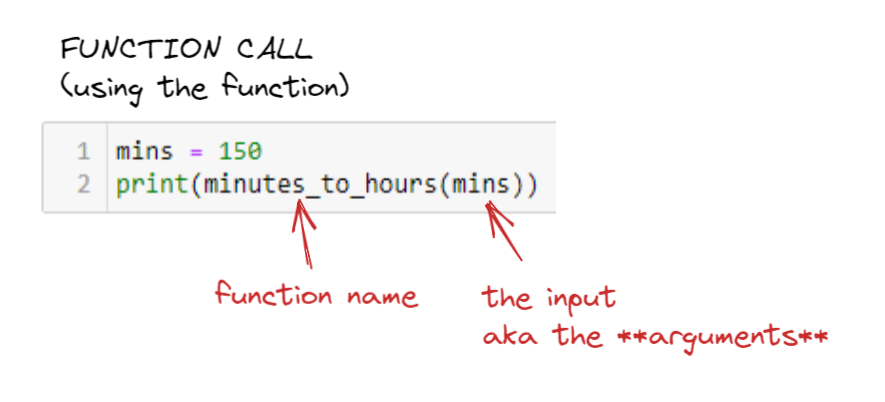

Function call#

In Python, function calls consist of at least:

A reference to the function name

One or more arguments (inside parentheses) to pass as input to the function (how many and what type is determined by the parameters in the function definition) Alongside other code

Let’s look at an example.

Suppose we have defined a function minutes_to_hours.

1def minutes_to_hours(minutes):

2 result = minutes/60

3 return result

As we’ve noted, when we run this code by itself, the code in the function definition doesn’t actually run: instead, Python is saving the function to memory and associating it with the label minutes_to_hours.

To run the code and use the function, we need to write code that calls (i.e., uses) the function, like this:

1mins = 150

2# call the minutes_to_hours function

3# with mins as an argument

4# and store the return value in the variable hours

5hours = minutes_to_hours(mins)

6print(hours)

2.5

Here, we have the function name (minutes_to_hours), and the argument mins being passed as input to the function, and code that takes the return value from the function and prints it out.

Here it is in pictures

What’s happening under the hood at this function call is:

Define the variable

minsand put the value 150 in itRetrieve the code associated with the function name

minutes_to_hoursand give itminsas an input argumentRun the code associated with the function name

minutes_to_hourswithminsas input, and return the resultPass that result to the

printfunction (yes, this is a function also!) as an input argument.

I recommend that you plug this code (and really all the other examples in this lecture) into pythontutor to step through it line by line. It really helps to build your intuition for what is happening.

Let’s look at another example pair.

1def bouncer(age):

2 result = age >= 21

3 return result

1your_age = 24

2come_in = bouncer(your_age)

3print(come_in)

True

Key idea: Arguments vs. parameters#

Parameters and arguments are easy to confuse. They both go in the parentheses after the function name. So what’s the difference?

It helps me to think of them as two sides of a special kind of variable assignment statement.

Parameters are the key variables in the function (what’s on the left side of an assignment statement). Arguments are the values you assign to those variables when you use the function (what’s on the right side of an assignment statement).

As a beginner, it’s common to wonder when you look at a function definition, “Where do the variables in the function get their value? I don’t see any assignment statements?” Arguments and parameters are the answer! At least some of the function’s variables are parameters, and they get their value from the arguments in the function call.

Let’s look at our minutes_to_hours example again, all together:

Here’s another example.

1def minutes_to_hours(minutes):

2 result = minutes/60

3 return result

4

5mins = 150

6hours = minutes_to_hours(mins)

7print(mins, "minutes is", hours, "hours")

150 minutes is 2.5 hours

In this program, when line 6 (hours = minutes_to_hours(mins)) executes, Python calls the function and passes the argument mins into the function and gives its value to the minutes parameter in the minutes_to_hours function.

If you want to make life easier for yourself when you’re still learning, you can make the mapping from arguments (on the right) to parameters (on the left) in a function call explicit in the function call code

1minutes_to_hours(minutes=90)

1.5

Equivalently:

1mins = 120

2minutes_to_hours(minutes=mins)

2.0

And:

1my_age = 19

2bouncer(age=my_age)

False

We’ll actually see this format (called “keyword arguments”) come back later on when we deal with more complicated functions, especially when we borrow code from other libraries! This is in contrast to the “positional argument” approach for simpler functions, where Python gives the 1st argument’s value to the 1st parameter’s value, 2nd argument to the 2nd parameter, and so on.

The basic pattern for using functions: DEFINE a function, use (CALL) a function#

So we’ve seen that there are two main parts of using functions in programming: 1) DEFINING a function, and then 2) CALLING (using) a function.

Here’s another example:

1# DEFINE a function that takes an input string and adds a specified number of characters to it

2def longer(inputString, howMany):

3

4 # create a string that is

5 # howMany characters long (by multiplying a single character string by that length)

6 toAdd = "a"*howMany

7

8 # concatenate that "toAdd" string to the input string

9 # and store in the result variable

10 result = inputString + toAdd

11

12 # return the result

13 return result

1# define a string

2s = "huzzah"

3

4# look at the current length of the string, using the len() function

5print("S is originally", len(s), "characters long. Here it is:", s)

6

7# define how much longer we want to make the string

8howMany = 3

9

10# CALL the longer() function to make a string that is that many characters longer than the string s

11# and store the return value in the new variable longer_s

12longer_s = longer(s, howMany)

13

14# look at the length of the longer string, using the len() function

15print("S is now", len(longer_s), "characters long after adding", howMany, "characters. Here it is:", longer_s)

S is originally 6 characters long. Here it is: huzzah

S is now 9 characters long after adding 3 characters. Here it is: huzzahaaa

The first chunk of code defines the function longer(). The second chunk of code calls the function on line 12 (longer_s = longer(s, howMany)).

This define-call sequence should look similar to our PCE structure: your solutions.py files define functions, and your tests.py files call those functions to test them with different inputs.

In later more complex programs, you often define a few functions at once, or borrow them from other bits of code, and then use them in a single program. You can also compose functions into larger functions!

Practice#

Let’s practice! Look at the following two chunks of code.

1# A

2def greet_user(username):

3 msg = "Hello " + username + "!"

4 return msg

1# B

2username = "Joel"

3greeting = greet_user(username)

4print(greeting)

Hello Joel!

Q: Which one is the function definition and which one is the function call?

A:

A is the function definition, and B has code that calls the function.

Q: Which line in the function call cell is actually calling the function?

A:

Line 3!

Let’s go back to our example sales cleaning program.

1# DEFINE the two sub-functions we need

2

3def clean_sale_number(saleNumStr):

4

5 # 1: remove dollar signs

6 saleNumStr = saleNumStr.replace("$", "")

7

8 # 2: remove the comma

9 saleNumStr = saleNumStr.replace(",", "")

10

11 # 3: convert to float

12 result = float(saleNumStr)

13

14 return result

15

16def compute_percent_change(lastYear, thisYear):

17

18 # first make the input numbers actually numbers

19 lastYear = clean_sale_number(lastYear)

20 thisYear = clean_sale_number(thisYear)

21

22 # then compute the percent change

23 result = ((thisYear - lastYear)/lastYear)*100

24 return result

25

26lastYear = "$500,000.35"

27thisYear = "$1,256,000.21"

28percentChange = compute_percent_change(lastYear, thisYear)

29print(percentChange)

151.19986616009368

Q: Where are the function calls?

A:

On line 28 (compute_percent_change(lastYear, thisYear)), but also inside the body of the compute_percent_change() function definition on lines 19 and 20, calling the clean_sale_number() function for both lastYear and thisYear variables!

How to define functions#

Writing a function from scratch#

There are a few main steps to follow:

Write the code that goes in the function (the steps)

Create a function definition

Write the skeleton of your function (

def, a name, parentheses,returnstatement)

Integrate your code into the function:

Fill out the parameters

Fill out the body of the code

Fill out the return statement

Run the function definition cell (this defines the function for Python)

Let’s look at an example together!

Let’s write a function that applies a discount to a sale, given the sale amount and the percentage discount.

Here is code that successfully computes a saleAmount after applying a discount

1saleAmount = 10.00

2percentageDiscount = 0.3

3

4saleAmount - saleAmount*percentageDiscount

7.0

And here is a function definition that encapsulates that code into a function apply_discount(), with saleAmount and percentageDiscount as input parameters, the main computation from above applying the discount in the function body, and then defining the return value as the finalAmount.

1def apply_discount(saleAmount, percentageDiscount):

2 finalAmount = saleAmount - saleAmount*percentageDiscount

3 return finalAmount

Here’s an example of how we can call that function, using our explicit argument-parameter notation from before.

1apply_discount(saleAmount=325.99, percentageDiscount=.2)

260.79200000000003

And another simple one: give me the area of a triangle, given its base and height.

Here’s functioning code:

1b = 3

2h = 2

30.5*b*h

3.0

And here’s a function definition for a function triangle_area() that has base and height (renamed here from b and h for readability, and we make sure to propagate that change to the function body), and area as the return value.

1def triangle_area(base, height):

2 area = 0.5*base*height

3 return area

Here’s an example of calling that function.

1triangle_area(base=5, height=10)

25.0

Converting existing code into a function#

The steps here are similar to writing from scratch, with the main difference that we:

Decide which of the variables in the existing code are inputs (parameters), and which ones are outputs (return values), then put those in the function definition and return statements.

Integrate the rest of the working code into the body of the function.

Here we’ve written the code for our substeps of converting the numbers into.. numbers. We know it works.

1# test number

2rawSale = "$600,153.25"

3

4# make the input numbers actually numbers

5# 1: remove dollar signs

6cleanSale = rawSale.replace("$", "")

7

8# 2: remove the comma

9cleanSale = cleanSale.replace(",", "")

10

11# 3: convert to float

12result = float(cleanSale)

13result # the output

600153.25

We can then encapsulate this into a function clean_sale_number(), with rawSale as the main input parameter, and the various operations cleaning the string in the function body, and the resulting float value as a return value.

1# 1. decide which variables are inputs/outputs, fill out function skeleton

2# 2. integrate rest of code into the body of the function

3

4# rawSale is input variable, so it's a parameter

5def clean_sale_number(rawSale):

6

7 # 1: remove dollar signs

8 cleanSale = rawSale.replace("$", "")

9

10 # 2: remove the comma

11 cleanSale = cleanSale.replace(",", "")

12

13 # 3: convert to float

14 result = float(cleanSale)

15 return result

We can then call the function like this:

1clean_sale_number(rawSale="$2,115,000")

2115000.0

Practice: converting code to functions#

For each exercise below, you are given working code with test inputs. Your task is to:

Identify which variables are inputs (parameters) and which are outputs (return values)

Write a function definition that encapsulates the code

Call your function with different arguments to verify it works

Exercise 1: Gym discount eligibility#

A gym offers a discount if you are either a student or over 65 years old. Here is working code that checks discount eligibility based on student status and age:

1isStudent = False

2age = 66

3

4isEligible = isStudent == True or age > 65

5print(isEligible)

True

Convert this into a function, then call it with different arguments to test it.

Hint

What is the key operation for the function body? The boolean expression checking isStudent and age

Here is some starter code (parameters and return statement are done, just fill in the body of the function!).

1def check_discount(isStudent, age):

2 # replace with your code

3 return result

4

5# test calls

6check_discount(isStudent=True, age=35) # True (student)

7check_discount(isStudent=False, age=66) # True (over 65)

8check_discount(isStudent=False, age=30) # False (neither)

600153.25

Exercise 3: Late penalty on an assignment#

Our syllabus has a late policy: 0.25% deduction per hour late. Here is working code that, given the number of hours late, the score, and the maximum score, calculates the final score after applying the late penalty:

1hoursLate = 3

2score = 30

3maximumScore = 50

4

5percentDeduction = hoursLate * 0.25

6pointsDeduction = percentDeduction / 100 * maximumScore

7finalScore = score - pointsDeduction

8print(finalScore)

Convert this into a function, then call it with different arguments to test it.

Hint

What are the inputs?

hours_late,score, andmaximumScoreWhat is the key operation for the function body? The lines of code computing the values for percentDeduction, pointsDeduction, and finalScore

What is the output? The final score after the late deduction

The body of the function should include the intermediate computation steps

Here is some starter code (fill in the right parameters, function body, return values, and function calls!)

1# add parameters

2def apply_late_penalty( ):

3 # add function body

4

5 # add return statement

6

7

8# test calls

9# add in arguments!

10apply_late_penalty()

11apply_late_penalty()

Exercise 4: Total bill with tip and tax#

You’re at a restaurant and want to compute the total bill including tip and tax. Here is working code that computes the total:

1mealCost = 45.00

2tipRate = 0.18

3taxRate = 0.06

4

5tipAmount = mealCost * tipRate

6taxAmount = mealCost * taxRate

7totalBill = mealCost + tipAmount + taxAmount

8print(totalBill)

Convert this into a function, then call it with different arguments to test it.

Hint

What are the inputs?

mealCost,tipRate, andtaxRateWhat is the key operation for the function body? The lines computing tipAmount, taxAmount, and totalBill

What is the output? The total bill

Here is some starter code (fill in the right parameters, function body, return values, and function calls!)

1# add parameters

2def total_bill( ):

3 # add function body

4

5 # add return statement

6

7

8# test calls

9# add in arguments!

10total_bill()

11total_bill()

Exercise 5: Distance traveled#

You want to compute how far a car travels, given its speed in miles per hour and the travel time in minutes. Here is working code that computes the distance:

1speedMph = 60

2timeMinutes = 90

3

4timeHours = timeMinutes / 60

5distance = speedMph * timeHours

6print(distance)

Convert this into a function, then call it with different arguments to test it.

Hint

What are the inputs?

speedMphandtimeMinutesWhat is the key operation for the function body? Converting minutes to hours, then multiplying speed by time

What is the output? The distance traveled

Here is some starter code (fill in the right parameters, function body, return values, and function calls!)

1# add parameters

2def distance_traveled( ):

3 # add function body

4

5 # add return statement

6

7

8# test calls

9# add in arguments!

10distance_traveled()

11distance_traveled()

Exercise 6: Sale price after discount and tax#

You want to compute the final price of an item after applying a discount and then adding sales tax. Here is working code that computes the final price:

1originalPrice = 80.00

2discountPercent = 25

3taxRate = 0.06

4

5discountAmount = originalPrice * (discountPercent / 100)

6discountedPrice = originalPrice - discountAmount

7taxAmount = discountedPrice * taxRate

8finalPrice = discountedPrice + taxAmount

9print(finalPrice)

Convert this into a function, then call it with different arguments to test it.

Hint

What are the inputs?

originalPrice,discountPercent, andtaxRateWhat is the key operation for the function body? The lines computing discountAmount, discountedPrice, taxAmount, and finalPrice

What is the output? The final price after discount and tax

Here is some starter code (fill in the right parameters, function body, return values, and function calls!)

1# add parameters

2def final_price( ):

3 # add function body

4

5 # add return statement

6

7

8# test calls

9# add in arguments!

10final_price()

11final_price()

Common errors when using functions#

Hard-coding parameters#

As a beginner, it’s common to look at a function definition, wonder why the variables don’t have assigned values, and write assignment statements to give them values inside the body of the function. We call this “hard-coding” the parameters (setting them to a fixed value, so they are no longer variables, but hard-coded values).

This is bad, because the function will no longer do its job of producing an output based on operations on the given inputs: it will only do operations on the hard-coded parameters, so it will produce the same result no matter what arguments are passed in during a function call!

As an example, the following function will always produce 2 as its output, no matter what arguments we pass in.

1def minus(x, y):

2 x = 3

3 y = 1

4 result = x - y

5 return result

This is because we are redefining x and y in the body of the function and giving them hard-coded values of 3 and 1. This makes the function ignore any argument values that are assigned to the parameters, and only use the hard-coded values, since the hard-coding happens after the arguments’ values are passed to the parameters when the function is called.

So this function will only subtract precisely 3 from 1, rather than subtracting any number y from x. For instance, this function call will yield 2 instead of 5, as we would expect:

1result = minus(10, 5)

2print(result)

Mismatching arguments and parameters#

Another common error is to call a function with a different number/order of arguments than the expected parameter number/order, which is a problem when you call functions in the common “positional argument” mode (just listing arguments in order of the parameters, as opposed to explicit “keyword arguments”)

For instance, if you define a function like this that expects x and y in that order:

1# example

2def minus(x, y):

3 result = x - y

4 return result

And call the function like this:

1minus(3)

When you run the program, it will halt with an error message: “TypeError: minus() missing 1 required positional argument: ‘y’”

The reason it fails with this TypeError in this case is because for the 2nd parameter, because it’s missing a corresponding 2nd argument.

The fix is to make sure that you have the same number of arguments as parameters. Again, writing out your function calls in explicit argument-parameter mappings can help make sure that you don’t make this error, like this:

minus(x=3, y=2)

But! You have to make sure you remember the name of the parameter and use that. Tradeoffs! :)

Missing / incorrect return statements#

Technically, from a syntax perspective, the return statement in a function definition is optional. Functions that don’t have return values are syntactically valid (legal code); they’re known as a “void functions”.

Confusingly, in Python, a void function still does return a value: a special Python value called

Nonethat represents “nothing”.Honestly, void functions kind of break the model of what a function should be (subcomponents in a larger program). In my experience, they are also quite rare in practice, except as, say, a main control loop, or the “main” procedure in a script. So, if you’re confused by void functions and find “regular” (also sometimes called “fruitful”) functions (with return values) easier to think conceptualize, I’m happy.

For now, I want you to pretend void functions don’t exist (i.e., do not write void functions; always have a return statement).

So why am I telling you this then?

You’ll see void functions in many Python tutorials. Often you’ll even learn about void functions before fruitful (or regular) functions. I think this may be because it has fewer moving parts? I’m not really sure.

Practically, too, if you leave out a

returnstatement, your code will still run! So the syntax is fine! But you’ll probably have made a semantic error (you meant to give the output of the function to some other piece of code, but the code you wrote isn’t actually doing that). This is a very common error for beginning programmers. So you if run into this, you’re in good company! If you’re pretty sure that the code in the body of the function is correct, but you’re confused by what happens when the function is used (e.g., it’s not giving you the value you expect), but the code runs, it’s a good idea to check yourreturnstatement!

An extremely common way to make this mistake is to write a print statement in the function body to produce output to you, the user, and declare that it works, but forget to write a return statement

Example: if we define the functions this way, without return statements, they will still run! BUT we won’t be able to use their results in a meaningful way, leading to an error if we try

1def tip(base, percentage):

2 result = base * percentage

3 print(result)

4

5def tax(base, tax_rate):

6 result = base * tax_rate

7 print(result)

This code will yield a strange TypeError complaining about trying to do math with an int and a NoneType (because the functions produce None return values by default!)

base = 3

tip_rate = 0.2

tax_rate = 0.08

total_check = tip(base, tip_rate) + base + tax(base, tax_rate)

print(total_check)

When you see this kind of error, it’s good practice to go back and check that your functions have return statements that produce the output you expect from the function.

NameErrors#

Functions are like variables, in that they are a way for Python to use a label (function name, variable name) to retrieve something from memory (a function, a value) to use in a program. So, just like variables, function calls can have a similar NameError, which just means that you’re asking Python to retrieve a function with a label, but there isn’t a box in memory with that label on it.

The same principles apply for variables as functions for this: make sure that your function is defined before you call it, and that the function call references the correct name of the function (not a misspelled one). Again, using autocomplete is your friend!

For instance, the following program will result in a NameError:

1def clean_sale_number(rawSale):

2

3 cleanSale = rawSale.replace("$", "")

4 cleanSale = cleanSale.replace(",", "")

5

6 result = float(cleanSale)

7 return result

8

9clean_sale(rawSale="$2,115,000")

Why? Because the function is defined with the label clean_sale_number, and we’re asking Python to go look for a function with the label clean_sale (which doesn’t exist!). Here, the fix would be to change line 9 to clean_sale_number(rawSale="$2,115,000").

Practice: debugging functions#

For each exercise below, there is a buggy function and a function call that produces incorrect output or an error. Your task is to:

Identify what type of error it is (hard-coded parameters, missing/incorrect return, or NameError)

Fix the bug

Exercise 1: Gym discount eligibility#

A gym offers a discount if you are either a student or over 65 years old. Debug the following program:

1def discount_eligibility(isStudent, age):

2 isStudent = False

3 age = 35

4 result = isStudent == True or age > 65

5 return result

6

7studentStatus = True

8customerAge = 35

9

10isEligible = discount_eligibility(isStudent=studentStatus, age=customerAge)

11print(isEligible)

The program call should print out True (the customer is a student), but it prints out False. What’s the bug and how do you fix it?

Hint:

Are the parameters in the function being used as expected by the code that calls it?

Exercise 2: Flour for cookies#

A recipe calls for 0.167 cups of flour for each cookie. Debug the following program that defines and calls a function to compute the desired number of cups for a given number of cookies to bake:

1def cups_per_cookie(num_cookies):

2 result = num_cookies * 0.167

3 print(result)

4

5target_num_cookies = 12

6

7num_cups = cups_per_cookie(num_cookies=target_num_cookies)

8print("We need", num_cups, "of flour to make", target_num_cookies, "cookies")

The program prints the correct number, but then also prints We need None of flour to make 12 cookies. Why does num_cups have the value None, and how do you fix it?

Hint:

Does the function definition produce the right outputs for the code that calls it?

Exercise 3: Late penalty#

Debug a program that calls a function to calculate the final score for an assignment after applying a late penalty (0.25% deduction per hour late):

1def apply_late_penalty(hours_late, score, maximum_score):

2 percent_deduction = hours_late * 0.25

3 points_deduction = percent_deduction / 100 * maximum_score

4 result = score - points_deduction

5 return score

6

7num_hours_late = 2

8initial_score = 55

9possible_score = 60

10

11final_score = apply_late_penalty(num_hours_late, initial_score, possible_score)

12print(final_score)

The program prints out 55 (the original score) instead of a reduced score. What’s the bug and how do you fix it?

Hint:

Does the function definition produce the right outputs for the code that calls it?

Exercise 4: Movie theater group discount#

A movie theater offers a group discount if a party has 5 or more people or if at least one member is a loyalty cardholder. Debug the following program that defines and calls a function to compute a group discount (if applicable) based on party size and loyalty cardholder status:

1def group_discount(group_size, has_loyalty_card):

2 group_size = 3

3 has_loyalty_card = False

4 result = group_size >= 5 or has_loyalty_card == True

5 return result

6

7num_in_group = 6

8loyalty_card = False

9discount = group_discount(num_in_group, loyalty_card)

10print("Discount eligibility for this group:", discount)

This prints False even though the group has 6 people (which is >= 5). What’s the bug and how do you fix it?

Hint:

Are the parameters in the function being used as expected by the code that calls it?

Exercise 5: Fitness tracker badge#

A fitness tracker awards a “goal achieved” badge if the user takes at least 10,000 steps. Debug the following program that defines and calls a function to check if a badge should be awarded based on steps so far:

1def goal_achieved(steps):

2 result = steps_today >= 10000

3 return result

4

5badge = goal_achieved(12000)

6print(badge)

Q: This produces a NameError: name 'steps_today' is not defined. What’s the bug and how do you fix it?

Hint:

Are the parameters in the function being used as expected by the code that calls it?

Exercise 6: Theme park ride eligibility#

A theme park allows kids to ride if they have a fast pass or are at least 48 inches tall. Debug the following program that defines and calls a function to check ride eligibility based on these factors:

1def ride_eligibility(fast_pass, height):

2 eligible = fast_pass or height >= 48

3 return eligible

4

5can_ride = ride_eligible(fast_pass=False, height=50)

6print("This person can ride:", can_ride)

Q: This produces a NameError: name 'ride_eligible' is not defined. What’s the bug and how do you fix it?

Hint:

Is the function you are trying to call appropriately defined?

Exercise 7: Tip calculator#

Debug the following program that calculates a total amount to pay, including tip:

1def tip(base_price, tip_prop):

2 result = base_price * tip_prop

3 print(result)

4

5check = 50

6tip_proportion = .18

7

8total = check + tip(base_price=check, tip_prop=tip_proportion)

9print("Total amount is", total)

Q: This prints 9.0 but then crashes with TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for +: 'int' and 'NoneType'. What’s the bug and how do you fix it?

Hint:

Does the function definition produce the right outputs for the code that calls it?